Haunting and Hosting

My original intentions for this post were complicated by three visitations.[1]In addition to the focus on Alexander, my plan was to engage with other Black and decolonial feminist thinkers that thematize haunting, such as Christina Sharpe, Saidiya Hartman, Denise Ferreira da … Continue reading They came in the form of active, disruptive pasts that I did not consciously or voluntarily summon, and in possession by memories, that neither fully belonged to myself nor to others. These visitations raised a host of personal, pedagogical, and philosophical concerns for me, calling me to think through my own relationship to race, to hauntings, and the obligation to counter institutional and historical-political forgetting.

When I was asked to write this post, I immediately knew I wanted to write about haunting and to think with M. Jaqui Alexander’s Pedagogies of Crossing. After reading the introduction I had gone straight to the chapter “Pedagogies of the Sacred.” In response to this “ancestrally co-written” text I wanted to write about possession, haunting, the sacred, and the duty of memory in ways that undo the anthropological and philosophical hierarchization of knowledge constitutive of colonial modernity, as well as of feminism and studies of gender and sexuality in the academy. I was struck by Alexander’s claim that: “the alignment of mind, body, and Spirit could be expected to assault the social practices of alienation wherever they may be practiced, whether within dominant religion, in the enclosure of the academy with its requirements of corporate time, or in day-to-day cultural prescriptions of disablement that call these Sacred practices and into question and challenge their value. Ultimately, this alignment cannot but provoke a confrontation with history” (320). This confrontation and the questions that follow strike me as difficult as they are crucial for feminist, decolonial, and Africana philosophy (and philosophers generally), for the recently opened Gender and Sexuality Studies Institute (GSSI) at The New School for Social Research (NSSR), and for the academy at large.

Alexander recounts how in 1989 she had “embarked on a project on the ways in which African cosmologies and modes of healing became the locus of an epistemic struggle in nineteenth-century Trinidad” (293). Alexander’s original intent was to “use an array of documents surrounding the trial, torture, and execution of Thisbe, one of those captured and forced into the crossing,” accused of “’sorcery’” as a way of exploring how “cosmological systems housed memory” (ibid.). Struggling with “writer’s block,” and the limitations of her own methodology, Alexander began in New York to “undertake linguistic spiritual work with a Bakôngo teacher so that I could follow Thisbe” (294). Alexander recounts how Thisbe’s spirit first visited her during a session of this spiritual work: “It was in that basement in the Bronx, New York, that she manifested her true name, Kitsimba – not the plantation name Thisbe – and placed it back into the lineage that she remembered and to which she belonged. From then I began the tentative writing of a history that was different from the one I had inherited, knowing that I could no longer continue to conduct myself as if Kitsimba’s life were not bound inextricably with my own” (ibid.). This visitation brought about important shifts in Alexander’s understanding of epistemology and research methodologies, not least because “the manner in which Kitsimba emerged to render her own account of her life,” was “diametrically opposed to my research plan of using her body as the ground for an epistemic struggle” (295). It also led her to earnestly pursue forms of spiritual practice and training in the traditions found in her native Trinidad, and across the African diaspora.

Following a rigorous analysis of the sacred focused on the cosmologies and practices of Vodou and Santería, Alexander asks: “What would taking the Sacred seriously mean for transnational feminism and related projects, beyond an institutionalized use value of theorizing marginalization?” (326). She suggests that “Taking the Sacred seriously would propel us to take the lives of primarily working-class women and men seriously” (328). That is, it would mean recognizing the value and skill of spiritual labor as a transformative practice of inner and outer self in ways that do not reduce it to “commodification,” “the service of capital,” and “any of the violent discourses of appropriation” (329). Such an engagement would not mean divorcing the spiritual from the social and the political. Instead, it would require that we see “Sacred praxis” as a mediation between the self, collectivities, and the world, that should be removed “from the category of false consciousness so that they can be accorded the real meaning they make in the lives of practitioners” (328).

1.

The first of the three ghosts caught me off guard. As I continued to read Pedagogies of Crossing, I turned to the chapter “Anatomy of a Mobilization,” and found an extended, detailed, and careful account of Alexander’s time as a visiting professor in Gender Studies at the New School (in the graduate division – what is now NSSR) and the “mobilization” that initially emerged in response to her precarious position as visiting faculty. The mobilization eventually became a cross-divisional, coalitional, fairly militant struggle that brought together students, faculty, and staff (including cleaners and security guards). This coalition all sought to confront and ameliorate the status of women, BIPOC, GLQT*, and working-class members of The New School, and the ways in which they and their labor were systematically devalued, tokenized, and exploited across the university. At issue was not only the hyperexploitation and precarity of certain kinds of tacitly racialized and gendered labor, but also the hierarchization and appropriation of knowledge manifest in patterns across The New School that while specific were expressive of broader trends in the late 90’s in higher education that combined neo-liberal marketization with older forms of power. The violent rifts and deep wounds that were created in the struggle between the administration and its allies, and the mobilization, contributed to the implosion of what was then the program in Gender Studies and Feminist Theory. On Alexander’s account: “rather than fight to continue a GSFT program that would incorporate the knowledges and presence of women of color, white feminist faculty would concede to its closure” (176). As I read these words I realized that this was the very program that had its afterlife in the institute that I was meant to be writing something for at that very moment. I had come upon this chapter by chance with no knowledge of what awaited me in it. How strange to encounter it then, just as I joined the NSSR, during a time of upheaval in the university as a whole which in many respects seemed to echo the moment Alexander has us relive in her painstaking narrative.

2.

The second ghost was more welcome since it seemed to offer me a way to continue with this post without my directly taking on the task of haunting (NSSR and GSSI) that it felt like Alexander had effectively passed on to me.

Fragmented and vaguely disturbing memories of the film Ghost returned to me one night as I tried to sleep. I must have seen it as a child. Originally released the year I was born, Ghost’s re-release this year was met with acclaim. According to a 2020 Guardian review, this “immortal meditation on love and grief (…) retains an innocence and earnestness that makes it delightfully comforting as ever.” If my memories were to believed Ghost was less a romance and more of a horror. Upon re-watching it I realized that what it unwittingly stages is the inextricability of white heterosexual bourgeois romance from the infinite horror of racial capital and white supremacy – and the absurd tragi-comedy that follows from the repression of this coupling.

Centered on Sam, a white male Wall Street banker, Ghost simultaneously summons and disavows many kinds of specters, specters that arguably haunt the white collective imaginary, and permeate sites of embodied and institutional memory in New York City. The plot is animated by specters of the Atlantic, that is by finance capital, and the virtual “blood money” trapped between bank accounts in a kind of digital ether for most of the film.

The fantasy of gentrification and unbridled property accumulation-speculation manifest in the central couple’s palatial, newly purchased warehouse is stalked by the urban decay and danger of the derelict downtown street which is the site of Sam’s death.[2]“Our ruins lie within the quick turnover of buildings, disappearing landmarks, and disposable homes, layered upon each other and over again’ (…) “And in the tradition of the symbolism of … Continue reading There is also the spectral presence of deviant black sexuality – the threatened rape of Sam’s white widow, Molly, by the Afro-Latino “mugger” who killed Sam, and the specter of queer interracial intimacy, between Molly, and the character Oda Mae Brown, the Black psychic who is haunted by Sam. And then there is the police. The police and an entire carceral apparatus of captivity are repeatedly summoned but never really arrive – instead they haunt the film as threat and promise.

The police put the present time of the narrative out of joint – as in the appearance of Oda Mae Brown’s “long” criminal record and the constriction of her future through the perpetual prospect of “doing time” again in the joint. These specters can all be understood as articulations of the ultimate ghost that haunts the film.

“Slave labor,” is Sam’s joking justification – offered in response to Molly’s question as to why he has invited his creepy banker friend, Carl, to their place without telling her just as they are moving in. Its entry is so fleeting and uncanny that one almost does not register it. Summoned as an offhand joke early on in the film, “slave labor,” is arguably the disavowed ground that underwrites Ghost’s “delightfully comforting” plot in which Black and brown bodies are presented as vessels to be rightly and justly used for the projection and fulfilment of white desires and needs.

Ghost is significant in the way that it reinforces a more general narrative that presents haunting as something to be resolved through reconciliation such that the past can be said to be properly past. Echoing trends regarding social and political reconciliation and “reparation,” in the film this resolution is on the condition that Oda Mae accept her own involuntary servitude.

But what if we were to follow Black and decolonial feminist treatments of haunting, and refuse the ruses of reconciliation, forgiveness, and progress that cloak the repetitions of the past in the present, and the correlations between haunting, violence, and injustice? What if we were to welcome the ghosts that haunt Ghost, TNS, and the city, as a way of exorcising the antiblackness and coloniality that arguably continue to animate them?

Such an exorcism might begin with the figure of Oda Mae Brown. With the afterlife of slavery that continues to animate the film and that means that Oda Mae (and by extension Black women more generally) are presented both as unwilling medium for white masculine desire and the maintenance of heteropatriarchal relations, and at the same time, as willing subjects characterized by sentimental self-sacrifice. A strange doublet that is perversely and memorably dramatized in the incipient sex scene and reworking of the zombie narrative – in which Oda Mae volunteers that Sam possess her body in order to use it as a surrogate for sexual relations with Molly. [3]This is an old trick. As Saidiya Hartman writes in Scenes of Subjection – in chattel slavery the selective attribution and simulation of consent, desire, agency to enslaved black women served … Continue reading And what of Oda Mae’s labors? Unacknowledged, uncompensated, socially reproductive labors? But what of her spiritual work? She is portrayed as a comic figure that preys on gullible Black and Latinx diasporic communities. The comedy stems in part from the assumed difference between “we” the enlightened audience and the vulnerable victims deprived of the powers of critical reason and easily duped by superstition and cheap magic tricks. Yet, in the film Oda Mae genuinely does have “the gift,” and the powers to resolve all of Sam’s unfinished business, as well as the knowledge (inherited from her grandmother) to explain why it is that Sam remains present even after death. Her knowledge is selectively utilized and dismissed for the ends of white masculine revenge throughout the film, but she is ultimately treated as an animate tool.

Thinking about Ghost in tandem with Alexander, I considered what exorcism might mean beyond the making visible of repetitive, structural violence and ongoing injustice. What shifts in academic and institutional knowledge would be required to see Oda Mae as epistemically credible? What would it mean to see women like her as carriers and creators of knowledge, and as spiritual practitioners performing important work that serves and builds communities, (such as Oda Mae’s Brooklyn constituency), – rather than as comic representatives and exploitative opportunists of “primitive” culture? The third visitation came when I was still thinking about the implications of these questions for gender and sexuality studies, and for the hierarchies of knowledge and power, that currently seem to be both retrenched and changing at The New School, and across higher education at large.

3.

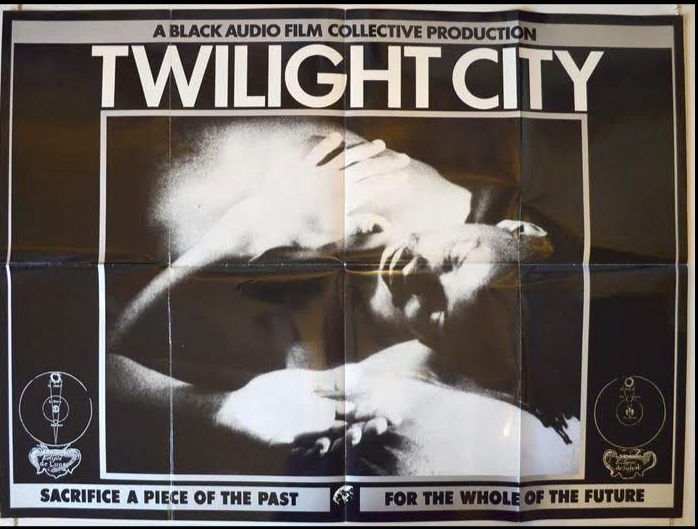

The final ghost arrived in the form of a screening of the Black Audio Film Collective’s Twilight City. Made a year prior, and on the other side of the Atlantic, Twilight City (1989) is like the negative of Ghost.

The narrative arc of Twilight City unfolds by way of the letters of a young, Black, queer woman to her estranged mother who had returned to Dominica some years ago. The mother has written to say that she now wants to come back to London. The protagonist’s response is a reflection on the possibilities of a future relationship between them in the city, and on the “New London,” that she attempts to see through her mother’s eyes – a London that is characterized by the refrain, “sacrifice a piece of the past for the whole of the future.” Like Ghost, Twilight City is a story of love that overcomes separation and forgetting. But the love of the latter spills over and already contains more than the boundaries of family or couple. Working through the past of the mother and daughter requires a reckoning with history and place that in turn entails sifting through ruins, graves, and wastelands. Twilight City refuses the progressive and reconciliatory relation to the past and dead that we get in Ghost. It does so through a reflection on the city that unfolds through a bricolage of archival footage, surrealist dream sequences, and interviews with theorists such as Homi Bhabha, Paul Gilroy, and Gail Lewis. The interviewees give personal accounts of their own early experiences of London, whilst analyzing the dynamics of dispossession, accumulation, violence, and memory that structure the past and (then) present of the rapidly changing city under Thatcher rule. In Twilight City, the ascent of the financial sector is spliced with the ghosts of the contemporary homeless, and with the exploited and forgotten victims of colonial and imperial violence. It thereby reverses the fantasy of the innocence and romance of the financial sector and of the refashioning of urban space that we are fed by Ghost.

It was uncanny to see Twilight City excavate the haunted psycho-geographies and identities of those migrant and non-white populations of the city of London, in which I was born and raised. The city which I have recently returned to and remained in longer than I had planned, and in which I am currently attempting to reorient myself. Director, John Akomfrah explains how the collective was “attracted to traditions (…) which feel as if they have a trauma to live down, that are possessed by memory, as if the present is possessed by a larger past that one has to tread through tentatively.” This may be a memory of gaps and silences, a memory that is my own. I have reconciled myself to non-belonging and to the impossibility of being definitively rooted in my past – to the past and places of my migrant grandparents (white South African and German), and to that of my father’s father who (we are fairly sure) was Somali (although he may have been mixed), born in Wales in 1925, he was eventually adopted by a white family and somehow ended up in London.[4]When revising this piece, I asked my dad about the details of my grandfather’s adoption. His text read: “Derek was born in 1925 in Newport and I believe his mum may have been Welsh but possibly … Continue reading There is a moment in Twilight City in which Somalis in Tower Hamlets discuss how, despite their long presence in Britain, due in part to their role as seamen for the British merchant navy (coincidentally, the paternal occupation listed on my grandfather’s birth certificate), they have been erased from national and institutional memory, and denied the requisite conditions and support that would enable the intergenerational transmission of culture. This testimony of loss felt the closest I could get to a part of my own inheritance and was voiced in the area I lived in for most of my young life. But it also reminded me of how erasure and memories are embedded in place and entangled with countless others.

Learning more about the Black Audio Film Collective, I was struck by their engagement with Benjamin (also close to my heart), and with “hauntologies” (the name of a 2012 exhibition by Akomfrah). But the film also made me think of a question that motivates Saidiya Hartman:“what does it mean to have this psychic inheritance of an experience for which one has no memory?” Hartman asks this question specifically in regards to the memories of slavery (it is worth underscoring that her relation to them is importantly different from mine.) Yet one strategy I’ve adopted is to follow the example of Hartman’s Lose Your Mother (a strategy that I now find closer to home in the example of Twilight City).That is, to turn to place and to landscape, as a way of honoring sedimented memories and excavating traces of those forgotten and dead that persist in the ruins and the detritus of history.

I end with a set of questions left to me by these three visitations.

My sense of a duty of remembrance and channeling dead, forgotten, and erased (in academic and social spaces) is in part due to my positionality as a white passing person of mixed racial descent. I see it as my duty to the counter collective forgetfulness spaces that often passes for authoritative knowledge and history. But it is no easy matter to be a good host to ghosts. What does it mean to host well? What is the role of agency, will, and identity in claiming and being claimed by the past and the dead? I’m thinking particularly of how to haunt and to host – about forms of ancestral, genealogical, collective and personal memory and the interwoven and difficult obligations and responsibilities this affords. What is or should be the relation between one’s identity, or positionality, and the production of knowledge with and for the dead? Said otherwise, what is the relation between “visitation rites,” on the one hand, and “visitation rights,” on the other?[5]

I take the distinction and play on visitation rites/rights from Eve Tuck’s collaborative work on haunting.

What does it mean to remember the dead who are not “yours”? And if, the opposite of dispossession is not possession, then what does the “yours” mean in this context?

In particular, Alexander pushes me to ask: How can one (as thinker, writer, teacher) respond to the call to remember and resurrect forgotten and erased counter-histories in a way that does not “preserve” trauma and cultures in “amber” while profiting off of them and disciplining them? To avoid preserving them “while ignoring the psychic, material, and spiritual costs of being put on display?” (121). What institutional or collective forms and structures would be necessary to facilitate and support the work of haunting, exorcising, visitation rights, and interrogations of the “rights” to this (work which, it seems, might be crucial for transnational-decolonial-intersectional-radical-queer feminisms)? What does it mean to be responsible for and to the ghosts of the institutions that we voluntarily and involuntarily inherit? And finally, what would a gender and sexualities studies institute look like that provides the conditions for such questions to be explored rigorously and carefully?

Romy Opperman is a postdoctoral fellow in philosophy, NSSR. Her work bridges the fields of Africana, decolonial, environmental, and continental philosophy. In Spring 21 she will teach a graduate seminar on Black Feminist Thought.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | In addition to the focus on Alexander, my plan was to engage with other Black and decolonial feminist thinkers that thematize haunting, such as Christina Sharpe, Saidiya Hartman, Denise Ferreira da Silva, and Eve Tuck. Their work draws on Black diasporic and Indigenous practices and traditions that take “wake work” and “being-with-the-dead,” seriously; at the same as it repurposes aspects of Walter Benjamin’s philosophy of history. Benjamin’s claim “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins,” is echoed in the waysthat their work navigates matters of cultural and ancestral memory, and confronts the inheritance of trauma, violence, and historic erasure. But from their work we also get the sense that neither will the living (most of all the “enemy”), be safe, until the dead, and the forms of violence that killed them, are properly laid to rest. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Our ruins lie within the quick turnover of buildings, disappearing landmarks, and disposable homes, layered upon each other and over again’ (…) “And in the tradition of the symbolism of horror, the ruin always points to the scene of ghost-producing violence. The ruin is not only the physical imprint of the supernatural onto architecture, but also the possessed or deluded people wandering amidst the ruin who fail to see its ruinous aspect. The idealistic homeowners who move into the haunted home; the humans who do not recognize the living dead until it is too late. In these layered always-ruining places, our ghosts haunt, and we are blind to it. They are ghosts birthed from empire’s original violence, the ghosts hidden inside law’s creation myth (Benjamin, 1986 p. 287), and the new ghosts on the way as our ruins refresh and mutate. They are specters that collapse time, rendering empire’s foundational past impossible to erase from the national present. They are a source of persistent unease.” Tuck, E. &; Ree, C. (2013). A glossary of haunting. In S. H. Jones, T.E. Adams; C. Ellis (Eds.) Handbook of autoethnography, 654 |

| ↑3 | This is an old trick. As Saidiya Hartman writes in Scenes of Subjection – in chattel slavery the selective attribution and simulation of consent, desire, agency to enslaved black women served to conceal and justify the nature of the (sexual) violence and situation of domination – a situation in which Black women could not consent. |

| ↑4 | When revising this piece, I asked my dad about the details of my grandfather’s adoption. His text read: “Derek was born in 1925 in Newport and I believe his mum may have been Welsh but possibly of mixed origin? Derek was baptised Hussein Mohammed I guess as a nod to his dad I understand he was adopted around the age of 6 (not sure) then his name was changed to Cox. It’s possible he spent time on a boys home b4 being adopted. I think then he moved to London as he used to talk about living in Warren Street and the old trams!” I’ve just started reading Hazel Carby’s Imperial Intimacies: A Tales of Two Islands – it’s been interesting thinking about this Black British history (longer than is usually imagined and with Wales as an important site) and indeed all the questions I raise here in relation to it. |

| ↑5 | I take the distinction and play on visitation rites/rights from Eve Tuck’s collaborative work on haunting. |